From Alpha to Understanding: A Dog Trainer’s Journey

I used to be one of those trainers who taught using dominance as my base for all behaviour. Even after I transitioned into positive training, when a dog would act up I would still use that as my behavioural model, pulling out the standard “he’s trying to be alpha and you need to be more assertive with him” or some line like that.

If a dog sleeping on the couch growled at someone that walked by and pet it, I would say, “He’s really challenging you. You need to be more assertive, a better leader. He doesn’t respect your authority.”

But gradually over the years my perspective changed and I really started listening to and hearing what the dogs were saying. Some might say I started to see what was right in front of me all along.

Where I used to say, “This dog is trying to be dominant” I now started looking at what the dog might be trying to communicate. I looked at environmental factors, experiences with the people and dogs he regularly interacted with, patterns of behaviour and, one of the most important, his body language.

When I started to notice the dogs body posture, I began to see that the dog snapping and snarling at the hand reaching down to pet it was actually leaning away from the person, with its ears back, tail tucked tight under its belly, paw raised and was averting its gaze, among other signals. All classic signals of fear, insecurity or discomfort. And quite the opposite of what one would expect a “dominant” dog to act like.

Now changing my perspective didn’t mean I developed a passive attitude. I still set boundaries, sometimes use aversives or punishment in my training and have rather high expectations of my dogs behaviour, probably more so than most. I am not a purely positive trainer. And, let’s face it, some days neither is my attitude.

But what this shift in perception meant for me was where I would previously have jumped to the label ‘dominant,’ now I would observe the actual dog in front of me to see where it might be coming from. After all, the motivation for any one behaviour in a dog can be as dynamic and unique as they are with people, but you can’t see what you aren’t looking for. My new labels became things like “confused,” “anxious,” “unclear of the owners expectations,” “uncomfortable,” “stressed,” or “in pain.” (Physical and medical conditions comprise a significant amount of behavioural issues, but tend to get overlooked if no one is looking beyond the dogs behaviour.)

Now I look at the sleeping dog on the couch who growls at the person trying to pet it and think “How would I respond if I were in a restful sleep and someone – uninvited – came and started messing with me?” The answer, unequivocally, is I would be very upset. Even my dogs know not to wake me up before the sun comes up.

And when I started to put training into terms that related the dogs experience to the same or a similar human experience, the dogs behaviour started to make more sense to me. And how I dealt with a particular issue changed even more dramatically. Instead of trying to fight to remain on top (I’m sure the dogs were laughing and saying, “Haha, we get it, you’re in charge. Quit trying so hard. Even WE don’t work to prove it to each other that much.”), it became about how I could teach the dog to enjoy the experience or about training the behaviour I needed instead of the one I was getting.

The positive side on the human end is that I noticed a shift in my human clients, as well. People became less tense and anxious that every move their dog made was an attempt to overthrow the government. They started to relax and enjoy life more with their dogs, especially the people who themselves were not naturally inclined to be “alpha” or authoritarian. I found other ways of dealing with dogs who seemingly had a big attitude that were just as effective, if not more so, than my old ways of training. Some clients were more than relieved when they found out they didn’t have to pretend to be someone with their dogs that they weren’t or simply didn’t want to be.

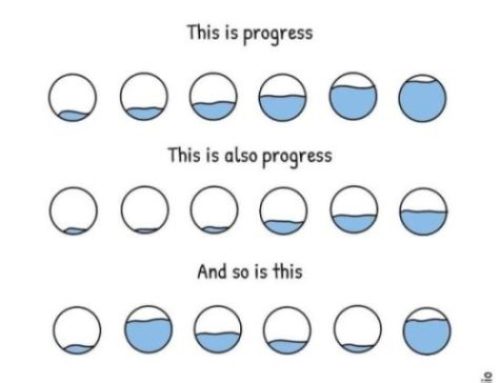

This shift for me didn’t happen in an instant. It took years. I was not particularly open to having what I believed to be true for so long challenged. (Okay, I’ll admit it, I wasn’t open even a little.) And let’s face it, it’s very unnerving to start from the ground up in unchartered territory using ideology where the result is unknown to you. And I’ll tell you my ego wasn’t thrilled either about the possibility of having been wrong.

But I eventually pushed through all that. It took listening, over and over, to, hearing and being open to seeing what some of my colleagues were telling me. Then it took finding the courage to change what I believed, trying a new approach and seeing for myself if it was actually true and gonna work.

But when the dog who previously snapped at the owner trying to pet it while it rested on the couch transitioned into a dog who’s tail wagged and eyes lit up when people approached it, I knew I was on the right track. And when the dog who previously flipped out so bad she needed to be sedated to have a nail trim transitioned into a calm, relaxed dog who would allow me to hold all of her paws and trim each of her nails while she watched, I was sold.

All it took was my willingness and curiosity to explore things from the dogs perspective instead of my own.

I know the idea about dogs and how they should be trained using an alpha attitude has been around for a long time, but I will leave you with this thought….

…..What if, after all these years, we were wrong?

Yours in training,

Darcie

www.facebook.com/CommuniCanine